Evaluation is a core part of the workings of artificial intelligence algorithms. It is something that can be built in, in the shape of specific segments of code. But it is also an additional human element which needs to complement and inform the subsequent use of any outputs of artificial intelligence systems.

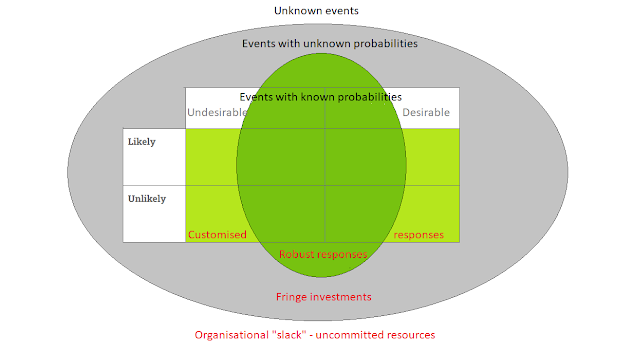

If we take supervised machine learning algorithms as one of the simpler forms of artificial intelligence, all of these have a very simple basic structure. Their operations involve the reiteration of search followed by evaluation. For example, we have a dataset which describes a number of cases, which could be different locations where a particular development intervention is taking place. Each of these cases have a number of attributes which we think may be useful predictors of an outcome we are interested in. And in addition, some of those predictors (or combinations thereof) might reflect some underlying causal mechanisms which would be useful for us to know about. The simplest form of machine learning will involve what is called an exhaustive or brute force search of each possible combination of those attributes (defined in terms of their presence or absence, in this simple example). Taking one combination at a time, the algorithm will evaluate whether it predicted the outcome or not, and then store that judgement. Reiterating that process, it will then compare the next judgement to this earlier judgement and replace that earlier judgement if the new one is better. And so on until all possible combinations have been evaluated and compared to previous judgement. In more complex machine learning algorithms involving artificial neural networks the evaluation and feedback processes can be much more complex, but the abstract description still fits.

What I'm interested in talking about here is what happens outside the block of code that does this type of processing. Specifically, with the products that are produced and how we humans can evaluate its value. This is territory where a lot of effort has already been expended, most noticeably on the subject of algorithmic fairness and what is known as the alignment problem. These could be crudely described as representing both short and long-term concerns respectively. I won't be exploring that literature here, interesting and important as it is.

What I will be talking about here is two examples of my own current experiments with the use of one AI application known as Claude AI, used to do some forms of qualitative data analysis. In the field that I work in, which is largely to do with international development aid programs, a huge amount of qualitative data i.e text is generated and I think it is fair to say that its analysis is a lot more problematic than when we are dealing with many forms of quantitative data. So the arrival of large language model (LLM) versions of artificial intelligence appears to offer some interesting opportunities for making some usable progress in this difficult area.

The text data that I have been working with as been generated by participants in a participatory scenario planning process, carried out using ParEvo.org, and implemented by the International Civil Society Centre in Germany this year. The full details of that exercise will be available soon in a ICSC publication. The exercise generated a branching tree structure of storylines about the future, built with 109 paragraphs of text, contributed by 15 participants, over eight iterations.What I will be describing here concerns two types of analysis of that text data.

Text summarisation

[this section has been redrafted] The first was a text summarisation task, where I asked Claude AI to produce one sentence headline summaries of each of these 109 texts. Text summarisation is a very common application of LLMs. This it did quickly, as usual, and the results looked plausible. But but by now I had also learned to be appropriately sceptical and was asking myself how 'accurate' these headlines were. I could examine each headline and its associated text, but this would take time. So I tried another approach.

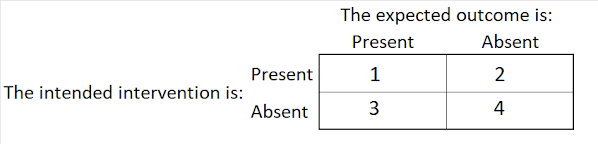

I opened up a new prompt window in Claude AI and uploaded 2 files. One containing the headlines, and the other containing each of the 109 texts preceded by an identification number. I then asked Claude AI to match each headline with the text that it best described, and to display the results using the ID number of the text (rather than its full contents) and the predicted associated headline. This process has some similarities with back translation. What I was interested in here was how well it could reassign the headlines to their original texts. If it did well this would give me some confidence in the accuracy of its analytic processes, and might obviate the need for a manual check up of the headlines' fit with content.

My first attempt was a clear failure, with classification accuracy of 21%, being far worse than chance. On examination this was caused by the way I had formated the uploaded data. The second attempt, using two separated data files, was more successful This time the classification accuracy was 63%. Given that the 27% error could occur at two stages (headline creation and headline matching) it could be argued that the classification error was more like half this value i.e 13.5% and so the classication accuracy was more like 76.5%. At this point it seemed worthwhile to also examine the misclassifications ( a back translation stage called reconciliation) - what headline was mismatched with what headline. An examination of the false classifications suggested that around 40% of the mismatches may have been because of words they had in common, despote the full headline being different.

Where does that leave me? With some confidence in the headline generation process, but could we do better? Could we find a better way to generate reproducable headlines...See further below where I talk about ensemble methods.

Content analysis

The second task was a type of content analysis. Because of a specific interest, I had separated a subset of the hundred nine paragraphs into two groups, the first of which had been the subject to further narrative development by the participants (aka surviving storylines), and the second being others which were not developed any further (aka extinct storylines). I asked Claude AI to analyse the subset of the texts in terms of three attributes: the vocabulary, the style of writing, and the genre. Then for each attribute, to sort the texts into two groups, and describe what each group had in common and how they differed from the other group. It then did so. Here is an image of its output.

My second strategy was another version of back translation, connecting concrete instances with pre-existing abstract descriptions. This time I opened a new prompt session, still within Claude AI, and uploaded a file containing the same subset of paragraphs, and then in the prompt window I copy and pasted the description of the attributes of the three sets of two groups identified earlier (without information on which text belnged to which group). I then asked Claude AI to identify which paragraphs of text fitted which of the 3 x 2 groups, which it did. I then collated the results of the two tasks in an Excel file, which you can see here below (click on image to magnify it). The green cells are where the predicted group matches the original group, and the yellow cells are where there were mismatches. The overall classification accuracy was 67%, whch is better than chance but not great either. I should also add that this was done with prompt information that included the IDs of the exemplars mentioned above (a format called "one-shot learning")

What was I evaluating when I was doing these "reverse translations"? It could probably be described as a test of, or search for, some form of construct validity. Was there any stable concept involved?

Ensemble methods

Given the two results reported above, which were better than chance, but not much better, what else could be done? There is one possible way forward, which might give us more confidence in the products generated by LLM analyses. Both Claude AI and ChatGPT4, and probably others, allow users to hit a Retry button, to generate another response to the same prompt. These will usually vary, and the degree of variation can be controlled by a parameter known as "temperature".

An ensemble approach in this context would be to generate multiple responses using the same prompt and then use some type of aggregation process to find the best result. Similar to 'wisdom of crowds" processes. In its simplest form this would, for example, involve counting the number of times each different headlines were proposed for the same item of text, and selecting one with the highest count. This approach will work where you have predefined categories as "targets". Those categories could have been developed inductively (as above) or deductively, from prior theory. It may even be possible to design a prompt script that include multiple genetration steps, and even the aggregation and evaluation stages.

But to begin with i will probably focus on testing a manual version of the process. I will report on some experiments with this approach in the next few days....

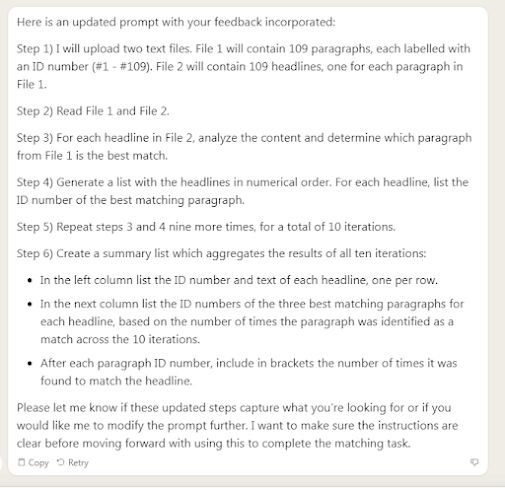

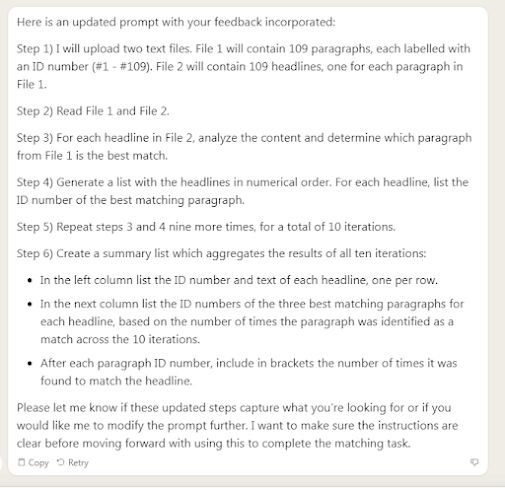

Update 02/09/23: A yet to be tested draft prompt that could automate the process

A lesson learned on the way: I initially wrote out a rough draft of a Claude AI prompt that might help automate the process I've described above. I then ask Claude AI to convert this into a prompt which would be understood and generate reliable and interpretable results. When it did this it was clear that part of my intentions had not been understood correctly (however you interpret the word understood). This could be just an epiphenomenon, in the sense of it only being generated by this particular enquiry. Or, it could point to a deeper or more structurally embedded analytic risk that would have consequences if I actually ask Claude AI to implement the rough draft in its original form (as distinct from simply refine that text as a prompt). The latter possibility concerned me, so I edited the prompt text that had been revised by Claude AI to remove the misunderstood part of the process. The version you see above is Claude AIs interpretation of my revised version, which I think will now work. Lets see,,,!

Update 03/09/23: It looks like the ensemble method may work as expected. Using 10 iterations only, which is a small number compared to how they are normally used, the classication accuracy increased to 84%. In the data displayed about numbers of time each predicted headline was matched to a given text there were 4 instances where there were ties. There were also 8 instances where the best match was still only found in less than 5 of the 10 iterations. More iterations might generate more definitive best matches and increase the accuracy rate. The correct match was already visible in the second and third ranking best matches of 4 of the 18 incorrectly matches headlines.

Another lesson learned, perhaps: Careful wording of prompts is important, the more explicit the instructions are the better. I learned to preface the word "match" with a more specific "analyze the content of all the numbered texts in File 1 and identify which one the headline best describes" . And careful formating of the text data files was also potentially important. making it clear where each text began and ended and removing any formating artifacts that could cause confusion.

And because of experiences with such sensitivities, I think i should re-do the whole analysis, to see if I generate the same or similar results!!!

Ensembles of brittle prompts?

I just came across this glimpse of a paper "Prompt Ensembles Make LLMs More Reliable" which is a different version of the idea I explored above. Here the prompt that is in use is also varied, from iteration to iteration.

Ensembles of brittel prompts?

.png)