A government has a new climate policy. It outlines how climate investments will be spread through a number of different ministries, and implemented by those ministries using a range of modalities. Some funding will be channelled to various multilateral organisations. Some will be spent directly by the ministries. Some will be channelled on to the private-sector. At some stage in the future this government wants to evaluate the impact of this climate policy. But before then it is been suggested that an evaluability assessment might be useful, to ask if how and when such an evaluation might be feasible.This could be a challenge to those with the task of undertaking the evaluability assessment. And even for those planning the Terms of Reference for that evaluability assessment. The climate policy is not yet finalised. And if the history of most government policy statements (that I have seen) has any lessons it is that you can't expect to see a very clearly articulated Theory of Change of the kind that you might expect to find in the design of a particular aid programme.

My provisional suggestion at this stage is that the evaluability assessment should treat the government's budget, particularly those parts involving funding of climate investments, as a theory of what is intended. And to treat the actual flows of funding that subsequently occur as the implementation of that theory. My naïve understanding of the budget is that it consists of categories of funding, along with subcategories and sub- subcategories, et cetera. In other words a type of tree structure involving a nested series of choices about where more versus less funds should go. So, the first task of an evaluability assessment would be to map out the theory i.e. the intentions as captured by budget statements at different levels of detail, moving from national to ministerial and then to small units thereafter. And to comment on the adequacy of these descriptions and and gaps that need to be addressed.

This exercise on its own will not be sufficient as an explication of the climate policy theory because it will not tell us how these different flows of funding are expected to do their work. One option would be to follow each flow down to its 'final recipient', if such a thing can actually be identified. But that would be a lot of work and probably leave us with a huge diversity of detailed mechanisms. Alternatively, one might do this on sampling basis, but how would appropriate samples be selected?

There is an alternative which could be seen as a necessity that could then be complemented by a sampling process. This would involve examining each binary choice, starting from the very top of the budget structure and asking 'key informants" questions about why climate funding was present in one category but not the other, or more in one category than the other. This question on its own might have limited value because budgeting decisions are likely to have a complex and often muddy history, and the responses received might have a substantial element of 'constructed rationality' . Nevertheless the answers could provide some useful context.

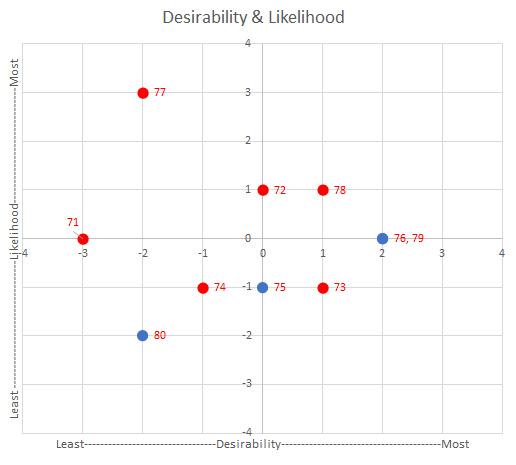

A more useful follow-up question would be to then ask the same informants about their expectations of differences in performance of the amount of climate financing via category X versus category Y. Followed by a question about how they expect to hear about the achievement of that performance, if at all. Followed by a question about what they would most like to know about performance in this area. Here performance could be seen in terms of the continuum of behaviours, ranging from simple delivery of the amount of funds as originally planned, to their complete expenditure, followed by some form of reporting on outputs and outcomes, and maybe even some form of evaluation, reporting some form of changes.

These three follow-up questions would address three facets of an evaluability assessments (EA): a) The ToC - about expected changes, b) Data availability , c) Stakeholder interests. Questions would involve two types of comparisons: funding versus no funding, and more versus less funding. The fourth EA question, about the surrounding institutional context, typically asks about the factors that may enable and/or limit an evaluation of what actually happened (more on evaluability assessments here).

There will of course be complications in this sort of approach.. Budget documents will not simply be a nested series of binary choices, at each level their work may be multiple categories available rather than just two. However informants could be asked to identify 'the most significant difference 'between all these categories, in effect introducing an intermediary binary category. There could also be a great number of different levels to the budget documents, with each new level in effect doubling the number of choices and associated questions that need to be asked. Prioritisation of enquiries would be needed, possibly based on a 'follow the (biggest amount of) money 'principle. It is also possible that quite a few informants will have limited ideas or information about the binary comparisons they are asked about. A wider selection of informants might help fill that gap. Finally there is the question of how to 'validate" the views expressed about expected differences in performance, availability of performance information and relevant questions about performance. Validation might take the form of a survey of a wider constituency of stakeholders within the organisation of interest, of the views expressed by the informants.

PS: Re this comment in the third para above: "And to treat the actual flows of funding that subsequently occur as the implementation of that theory" One challenge the EA team might find is that while it may have accessed to detailed budget documents, in many places it may not yet be clear where funds have been tagged as climate finance spending. That itself would be an important EA finding.

To be continued...

.jpg)