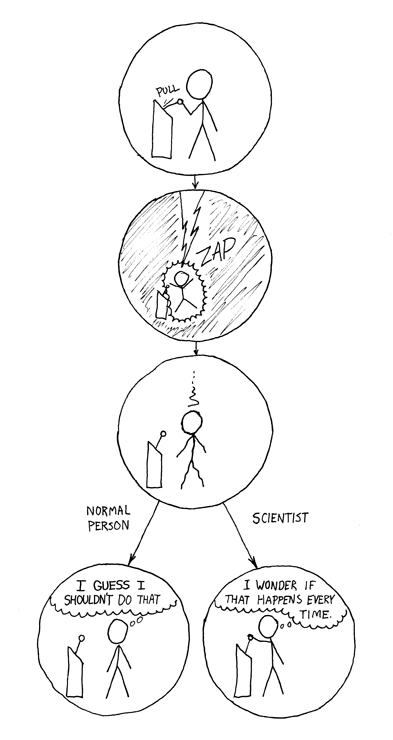

This week the Swedish Evaluation Society (SVUK) is holding its annual conference. I took part in a session today on Theories of Change. The first part of my presentation summarised the points I made in a 2018 CEDIL Inception Report titled 'Theories of Change: Technical Challenges with Evaluation Consequences'. Following the presentation I was asked by Gustav Petersson, the discussant, whether we should pay more attention to the process of generating diagrammatic Theories of Change. I could only agree, reflecting that for example it was not uncommon that a representative of a conference working group might summarise a very comprehensive and in-depth discussion in all too brief and succinct terms when reporting back to a plenary. Leaving out, or understating, the uncertainties , ambiguities and disagreements. Similarly the completed version of a diagrammatic Theory of Change is likely to suffer from the same limitations ... being an overly simplified version of a much more complex and nuanced discussions between those involved in its construction that went on beforehand.

Later in the day I was reminded of this section in the Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy where Vroomfondel, representing a group of striking philosophers said '"That's right!" and shouted , "we demand rigidly defined areas of doubt and uncertainty!"

I'm inclined to make a similar kind of request of those developing Theories of Change. And of those subsequently charged with assessing the evaluability of the associated intervention, including its Theory of Change. What I mean is that the description of the Theory of Change should make it clear which various parts of the theory the owner(s) of that theory are more confident in verses less confident. Along with descriptions of the nature of the doubt or uncertainty and its causes e.g. first-hand experience, or supporting evidence (or lack of) from other sources.

Those undertaking an evaluability assessment could go a step further and convert various specific forms of doubt and uncertainty into evaluation questions that could form an important part of the Terms of Reference for an evaluation. This might go some way to remedying another problem discussed during the session, which is the all too common (in my experience) phenomena of Terms of Reference only making generic references to an intervention's Theory of Change. For example, by asking in broad terms about "what works and in what circumstances". Rather than the testing of various specific parts of that theory, which would arguably be more useful, and better use of limited time and resources.

The bottom line: The articulation of a Theory of Change should conclude with a list of important evaluation questions. Unless there are good reasons to the contrary, those questions should then appear in the Terms of Reference for a subsequent evaluation

PS: Vroomfondel is a philosopher. He appears in chapter 25 of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, along with his collegue Majikthise, as a representative of the Amalgamated Union of Philosophers, Sages, Luminaries and Other Thinking Persons (AUPSLOTP; the BBC TV version inserts 'Professional' before 'Thinking'). The Union is protesting about Deep Thought, the computer which is being asked to determine the Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe and Everything. See https://hitchhikers.fandom.com/wiki/Vroomfondel