Background

I and others are providing technical advisory support to the evaluation of a large complex multilateral health intervention, one which is still underway. The intervention has multiple parts implemented by different partners and the surrounding context is changing. The intervention design is being adapted as time moves on. Probably not a unique situation.

The proposal

As one of a number of parts of a multi-year evaluation process I might suggest the following:

1. A timeline is developed describing what the partners in the intervention see as key moments in its history, defined as where decisions have been taken to change , stop or continue, a particular course(s) of action.

2. Take each of those moments as a kind of case study, which the evaluation team then elaborates in detail: (a) the options that were discussed, and others not, (d) the rationales for choosing for and against those discussed options at the time, (d) the current merit of those assessments, as seen in the light of subsequent events. [See more details below]

The objective?

To identify (a) how well the intervention has responded to changing circumstances and (b) any lessons that might be relevant to the future of the intervention, or generalisable to other similar intervention.

This seems like a form of (contemporary and micro-level) historical research, investigating actual versus possible causal pathways. It seems different from a Theory of Change (ToC) based evaluation, where the focus is on what was expected to happen and then what did happen. Whereas with this proposed historical research in to decisions taken the primary reference point is what did happen, then what could have happened.

It also seems different from what I understand is a process tracing form of inquiry where, I think, the focus is on particular hypothesised causal pathway. Not the consideration of multiple alternative possible pathways, as would be the case within each of a series of decision making case studies proposed here. There may be a breadth rather than depth of inquiry difference here.[Though I may be over-emphasising the difference here, ...I am just reading Mahoney, 2013 on use of process tracing in historical research]

The multiple possible alternatives that could have been chosen are the counterfactuals I am referring to here.

The challenges?

As Henry Ford allegedly said "History is just one damn thing after another" There are way too many events in most interventions where alternative histories could have taken off in a different direction. For example, at a normally trivial level, someone might have missed their train. So to be practical but also systematic and transparent the process of inquiry would need to focus on specific types of events, involving particular kinds of actors. Preferably where decisions were made about courses of action. Such as Board Meetings.

And in such individual settings how wide should the should the evaluation focus be? For example, only on where decisions were made to change something, or also where decisions were made to continue doing something? And what about the absence of decisions being even considered, when they might have been expected to be considered. That is, decisions about decisions.

Reading some of the literature about counter-factual history, written by historians, there is clearly a risk of developing historical counterfactuals that stray too far from what is known to have happened, in terms of imagined consequences of consequences, etc. In response, some historians talk about the need to limit inquiries to"constrained counterfactuals" and the use of a "Minimal Rewrite Rule". [I will find out more about these]

Perhaps another way forward is to talk about counter-factual reasoning, rather than counterfactual history (Schatzberg, 2014) . This seems to be more like what the proposed line of inquiry might be all about i.e. how the alternatives to what actually was decided and happened were considered (or not even considered) by the intervening agency. But even then, the evaluators' assessments of these reasonings would seem to necessarily involve some exploration of consequences of these decisions, and only some of which will have been observable, and others only conjectured.

The merits?

When compared to a ToC testing approach this historical approach does seem to have some merit. One of the problems of a ToC approach, particularly when applied to a complex intervention is the multiplicity of possible causal pathways, relative to the limited time and resources available available to an evaluation team. Choices usually need to be made, because not all avenues can be explored (unless some can excluded by machine learning explorations or other quantitative processes of analysis).

However, on reflection, the contrast with a historical analysis of the reality of what actually happened is not so black and white. In large complex programmes there are typically many people working away in parallel, generating their own local and sometimes intersecting histories. There is not just one history from within which to sample decision making events In this context a well articulated ToC may be a useful map, a means of identifying where to look for those histories in the making.

Where next

I have since found that that the evaluation team has been thinking along similar lines to myself i.e. about the need to document and analyse the history of key decisions made. If so, the focus now should be on elaborating questions that would be practically useful, some of which are touched on above. Including:

1. How to identify and sample important decision making points

At least two options here:

1. Identify a specific type of event where it is know that relevant decisions are made. E.g, Board Meetings. This is a top-down deductive approach. Risk here is that many decisions will (and have to be) made outside and prior to these events, and just receive official authorisation at these meetings. Snowball sampling backwards to original decisions may be possible...

2. Try using the HCS method to partition the total span of time of interest into smaller (and nested) periods of time. Then identify decisions that have generated the differences observed between these periods (which will sought about the intervention strategy). This is a more bottom-up inductive approach.

2. How to analyses individual decisions.

The latter includes interesting issues such as how much use should be made of prior/borrowed theories about what constitute good decision making, versus using a more inductive approach that emphasises understanding how the decisions were made within their own particular context. I am more in favor of the latter at present

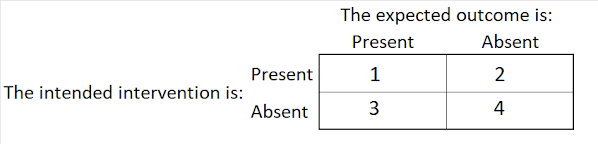

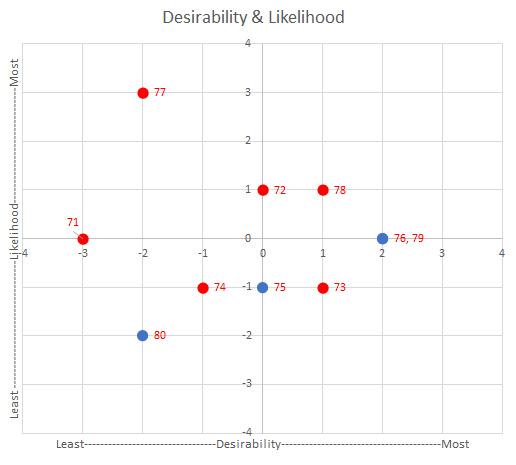

Here is a VERY provisional framework/checklist for what could be examined, when looking at each decision making event:

In this context it may also be useful to think about a wider set of relevant ideas like the role of "path dependency" and "sunk costs"

3. How to aggregate/synthesise/summarise the analysis of multiple individual decision making cases

This is still being thought about, so caveat emptor:

Objectives were to identify:

(a) how well the intervention has responded to changing circumstances.

Possible summarising device? Rate each decision making event on degree to which it was optimal under the circumstances. Backed by a rubric explaining rating values.

Cross tabulate these ratings against a ratings of the subsequent impact of the decision that was made? An "Increased/decreased potential impact" scale.? Likewise supported by a rubric (i.e. annotated scale).

(b) any lessons that might be relevant to the future of the intervention, or generalisable to other similar intervention.

Text summary of implications identified from the analysis of each decision making event, with priority to more impactful/consequential decisions?

Lot more thinking yet to be done here...

Miscellaneous points of note hereafter...

Postscript 1: There must be a wider literature on this type of analysis, where there may be some useful experiences. "“Ninety per cent of problems have already been solved in some other field. You just have to find them.” McCaffrey, T. (2015) New Scientist.

Postscript 2: I just came across the idea of an "even if..." type counterfactual. As in "Even if I did catch the train, I would still not have got the job". This is where when an imagined action, different from what really what happened, still leads to the same outcome as when the real action took place.

.jpg)