Cynefin

Lots of people seem to like the

Cynefin Framework.

Jess Dart and Patricia Rogers are some of my friends and colleagues of mine who have expressed a liking for it. It was one of the subjects of discussion in the recent

Evaluation Revisited conference in Utrecht in May. Why don’t I like it? There are three reasons...

Usually matrix classifications of possible states are based on the intersection of two dimensions. They can provide good value because combining two dimensions to generate four (or more) possible states is a compact and efficient way of describing things. Matrix classifications have

parsimony.

But whenever I look at descriptions of the Cynefin Framework I can never see, or identify, what the two dimensions are which give the framework its 2 x 2 structure, and from which the four states are generated. If they were more evident I might be able to use them to identify which of the four states best described the particular conditions I was facing at a given time. But up to now I just have to make a best guess, based on the description of each state. PS: I have been told by someone recently that Dave Snowden says this is not a 2x2 matrix, but if so, why is presented like one?

My second concern is the nature of the connection between this fourfold classification and other research on complexity, beyond the field of management studies and consultancy work. IMHO, I don’t think there is much in the way of a theoretical or empirical basis for it, especially when Dave’s fifth state of “disorder”, is placed in the centre. This may be the reason why the two axes of the matrix I mentioned above have not been specified, ...because they have not yet been found.

My third concern is that I don’t think the fourfold classification has much discriminatory power. Most the situations I face, as an evaluator, could probably be described as complex. I don’t see many really chaotic ones, like gyrating stock markets or changeable weather patterns, nor do I see many that could be described as simple, or just complicated. Except perhaps when dealing with single person’s task, not involving interactions with others. Given the prevalence of complex situations, I would prefer to see a matrix that helped me discriminate

between different forms of complexity, and their possible consequences.

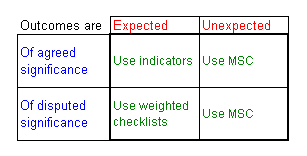

Stacey

This brings me to Stacey's matrix, which does have two identifiable dimensions shown above: certainty (i.e. the predictability of events) and the degree of agreement over those events. Years before I had heard of "Stacey's matrix"" I had found the same kind of 2 x 2 matrix a useful means of describing four different kinds of possible development outcomes which had different implications for what sort of M&E tools would be most relevant. For example, by definition you cannot use predefined indicators to monitor unpredictable outcomes (regardless of whether we agree or disagree on their significance). However methods like MSC can be used to monitor these kinds of change. And a good case could be made for more attention to the use of historian's skills, especially to respond to unexpected events that are of dispute meaning. More recently I argued that

weighted checklists are probably the most suitable for tracking outcomes that are predictable but where there is not necessary any agreement about their significance. A

quote from Patton could be hijacked and used here "

These distinctions help with situation recognition so that an evaluation approach can be selected that is appropriate to a particular situation and intervention, thereby increasing the likely utility -and actual use- of the evaluation" (page 85, Developmental Evaluation)

From what I have read I think Ralph Stacey also produced the following more detailed version of his matrix:

This has then been simplified by

Brenda Zimmerman, as follows

In this version simple, complicated complex and anarchy (chaos) are in effect part of a continuum, involving different mixes of agreement and certainty. Interestingly, from my point of view, the category taking up the most space in the matrix is that of complexity, echoing my gut level feeling expressed above. This feeling was supported when I read Patton's three examples of simple, complicated and complex (page92, ibid), based on Zimmerman. The simple and complicated examples were both about making

materials do what you wanted (cake mix and rocket components), whereas the complex example was about child rearing i.e. getting

people to do what you wanted. More interesting still, the complex example was raising a couple of children in family, in other words a

small group of people.So anything involving more people is probably going to be a whole lot more complex. PS: And interestingly along the same lines, the difference between simple and complicated was a physical task involving

one person (following a recipe) and one involving

large numbers of people (sending a rocket into space)

Another take on this is given by

Chris Rodgers comments on Stacey’s views:

“Although the framework, which Stacey had developed in the mid-1990s, regularly crops up in blogs, on websites and during presentations, he no longer sees it as valid and useful. His comment explains why this is the case, and the implications that this has for his current view of complexity and organizational dynamics. In essence, he argues that

- life is complex all the time, not just on those occasions which can be characterized as being “far from certainty” and “far from agreement” …

- this is because change and stability are inextricably intertwined in the everyday conversational life of the organization …

- which means that, even in the most ordinary of situations, something unexpected might happen that generates far-reaching and unexpected outcomes …

- and so, from this perspective, there are no “levels of complexity” …

- nor levels in human action that might usefully be thought of as a “system”.

Well maybe,… but this is beginning to sound a bit too much like the utterances of a Zen master to me :-) Like Rodgers, I hope we can still make

some kind of useful distinctions re complexity.

Back to Snowden

Which brings me back to a more recent statement by Dave Snowden, which to me seems more useful than his earlier Cynefin Framework. In his presentation at the Gurteen Knowledge Cafe, in early 2009,

as reported by Conrad Taylor, "Dave presented

three system models: ordered, chaotic and complex. By ‘system’ he means networks that have coherence, though that need not imply sharp boundaries. ‘Agents’ are defined as anything which

acts within a system. An agent could be an individual person,or a grouping; an idea can also be an agent, for example the myth-structures which largely determine how we make decisions within the communities and societies within which we live."

- "Ordered systems are ones in which the actions of agents are constrained by the system, making the behavior of the agents predictable. Most management theory is predicated on this view of the organisation."

- Chaotic systems are ones in which the agents are unconstrained and independent of each other. This is the domain of statistical analysis and probability. We have tended to assume that markets are chaotic; but this has been a simplistic view."

- "Complex systems are ones in which the agents are lightly constrained by the system, and through their mutual interactions with each other and with the system environment, the agents also modify the system. As a result, the system and its agents ‘co-evolve’. This, in fact, is a better model for understanding markets, and organisations.”

This conceptualization is simpler (i.e. has more economy) and seems more connected with prior research on complexity. My favorite relevant quote here is Stuart Kauffman’s book:

At home in the Universe: The search for the laws of complexity (p86-92) where he describes the behavior of electronic models of networks of actors (with on/off behavior states for each actor) moving from simple to complex to chaotic patterns,

depending on the number of connections between them. As I read it, few connections generate ordered (stable) network behavior, many connections generate chaotic (apparently unrepeating) behavior, and medium numbers (where N actors = N connections) generate complex cyclical behavior. (

See more on Boolean networks).

This relates back to conversation that I had with Dave Snowden in 2009 about the value of a network perspective on complexity, in which he said (as I remember) that relationships within networks can be seen as constraints. So, as I see it, in order to differentiate forms of complexity we should be looking at the nature of the specific networks in which actors are involved: Their number, the structure of relationships, and perhaps the extent to which the actors have own individual autonomy i.e. responses which are not specific to particular relationships (an attribute not granted to “actors” in the electronic model described).

My feeling is that with this approach it might even be possible to link this kind of analysis back to Stacey’s 2x2 matrix. Predictability might be primarily a function of connectedness, and therefore more problematic in larger networks where the number of possible connections is much higher. The possibility of agreement, Stacey’s second dimension, might be further dependent the extent to which actors’ have some individual autonomy within a given network structure.

To be continued…

PS 1:Michael Quinn Patton's book on

Developmental Evaluation has a whole chapter on "Distinguishing Simple, Complicated, and Complex". However, I was surprised to find that despite the book's focus on complexity, there was not a single reference in the Index to "networks". There was one example of a network model (Exhibit 5.3) , contrasted with a Linear Program Logic Model..." (Exhibit 5.2) in the chapter on Systems Thinking and Complexity Concepts. [I will elaborate further

here]

Regarding the simple, complicated and complex, on page 95 Michael describes these as "sensitising concepts, not operational measurements" This worried me a bit, but it is an idea with a history (

Look here for other views on this idea). But he then says "The purpose of making such distinctions is driven by the utility of situation recognition and responsiveness. For evaluation this means matching the evaluation to the nature of the situation" That makes sense to me, and is how have I tried to use the simple version of the Stacey Matrix (using dimensions only). However, Michael then goes on to provide, perhaps unintentionally, evidence of how useless these distinctions are in this respect, at least in their current form. He describes working with a group of 20 experienced teachers to design an evaluation of an innovative reading program. "They disagreed intensely about the state of knowledge concerning how children learn to read..Different preferences for evaluation flowed from different definitions of the situation. We ultimately agreed on a mixed methods design that incorporated aspects of both sets of preferences". Further on in the same chapter, Bob Williams is quoted reporting the same kind of result (i.e conflicting interpretations), in a discussion with health sector workers. PS 25/8/2010 - Perhaps I need to clarify here - in both cases participants could not agree on whether the situation under discussion was simple, complicated or complex, and thus these distinctions could not inform their choices of what to do. As I read it, in the first case the mixed method choice was a compromise, not an informed choice.

PS 2: I have also just pulled Melanie Mitchell's "

Complexity: A Guided Tour" off the shelf, and re-scanned her Chapter 7 on "

Defining and Measuring Complexity". She notes that about

40 different measures of complexity have been proposed by different people. Her conclusion, 17 pages later, is that "The diversity of measures that have been proposed indicates that the notions of complexity that we're trying to get at have many different interacting dimensions and probably cant be captured by a single measurement scale" This is not a very helpful conclusion. But I noticed that she does cite earlier what seem to be three

categories of measures that cover many of the 40 or so measures: These are: 1. how hard the object or process is to describe?, 2. How had it is to create?, and 3. What is its degree of organisation?

PS 3: I have followed up John Caddell's advice to read

a blog post by Cynthia Kurtz (a co-author of the IBM Systems Journal paper on Cynefin) recalling some of the early work around the framework. In that post was the following version of the Cynefin Framework included in the oft-mentioned "

The new dynamics of strategy: Sense-making in a complex and complicated world" published in the IBM SYSTEMS JOURNAL, VOL 42, NO 3, 2003.

In her explanation of the origins of this version she says it had two axes: "the degree of imposed order" and "the degree of self-organization." This I found interesting because these dimension have the potential to be measurable. If they are measurable, then the actual behavior of four identified systems could be compared. And we could then ask "Does their behavior differ in ways that have consequences for managers or evaluators?" I have previously speculated that there might be

network measures that could describe these two measures: network density and network centrality. Network centrality could be the x axis, being low on the left and high on the right, and network density could be the y axis, low on the bottom and high on the top. How well the differences in these four types of network structures might capture our day-to-day notion of complexity is not yet clear to me. As mentioned way above, density does seem to be linked to differences between simple, complex and chaotic behavior. Maybe differences in centrality moderate/magnify the consequences of different levels of network density?

PS 4 (April 2015: For more reading on this subject that may be of interest, see

Diversity and Complexity by Scott E Page, Princeton, 2011